- Home

- Nnedi Okorafor

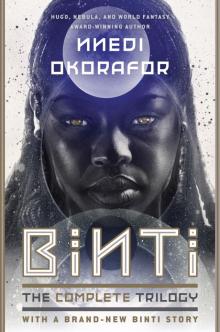

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Page 9

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Read online

Page 9

“Wish visiting home didn’t have to include interstellar travel,” I mumbled to myself. Even as I got older everyone pulled back from me, I thought. Even my best friend Dele. I don’t think even he realized he was doing it. We were all falling into our roles, our destiny in the community. We were no longer free . . . and that was when my musings crossed that toxic boundary I’d crossed in Professor Okpala’s office earlier in the day. It was like treeing, but it was carrying me instead of me carrying it. I couldn’t get off the ship. I’d never been in space before and everyone around me was dead and I was only alive because of an intricate old dead device from a mystery metal.

I gasped and pressed my left hand to the shuttle’s large round window, my bandaged hand to my chest. My heart was punching at my ribcage.

“Why are you so tense?”

I was still not used to the sound and feel of the Meduse language and, thankfully, its vibration cut right through to me.

“Tense?” I asked. “D-d-do I look tense?”

“Yes” Okwu said. “You’ve been tense since we left Math City. That’s how I knew to come find you near your professor’s office.”

“I . . . was tense . . . I’m tense . . . I . . .” I giggled nervously, but even as the sound escaped me, I was seeing Heru’s chest exploding, yet again. I turned squarely to Okwu and I saw all those Meduse around me only held from killing me because something about my edan was poison to them. I resisted the urge to grab my edan from my pocket and thrust it at Okwu.

“Binti! Hey!”

I looked around, glad for a reason to pull my eyes from Okwu.

“Back here! Behind you!” It was Haifa. She was sitting several seats back with her roommate, a Person who I only knew as the Bear.

I waved, pushing a smile on my face. “No, no,” I said, when I saw her get up to come over to us. “It’s too packed.”

But Haifa was never one to avoid motion just because it was difficult. I think she actually liked the challenge. The Bear got up, too, though I didn’t know why. Over the weeks, I’d run into the Bear several times in the bathroom, in the study room, eating lunch on the steps and not once had she spoken to me. When Haifa got to us, she boldly shoved the two Meduse-like people out of the way to get to my seat. The two People simply floated back to make space for them. I’ll never get over the way Oomza Uni people do that on the shuttle. It’s considered polite behavior. I dreaded the day someone shoved me aside to pass and I went sprawling to the floor.

“Okwu,” Haifa said.

“Haifa,” Okwu said.

“You know each other?” I asked.

“We’re in all the same classes,” Haifa said.

“I find Haifa annoying” Okwu said. “But I suspect she will make great weapons.”

Haifa laughed loudly. “Even a Meduse is threatened by me because I’m just that genius. Everything is right in our universe.”

Okwu blasted out a large cloud of gas and Haifa and I coughed. The adult human-sized giant bail of rough brown hair that was the Bear merely shuddered. “No Meduse would fear you, Haifa,” Okwu said, its dome vibrated with laughter.

I tuned them out for the moment because I was climbing into the tree as I looked out the window. The shuttle was slowing down; we’d reached our stop. My thoughts went inward as I decided. To clear my mind, I worked an equation through my mind, Euler’s identity, eiπ + 1 = 0, one of the most gorgeous formulas I knew. An equation that showed the connection between the most fundamental numbers in mathematics. It was the formula that connected all things because everything is mathematics. I slowly turned to Haifa as she said, “Come on, you two, this is our stop. Okwu, we’ll see what’s what when we get to exams. You know at the end of the year, we get to battle each other with the weapons we built?”

Okwu’s dome thrummed harder and the three of them began to move to the front of the train. I didn’t move. It was Okwu who stopped first. “Binti,” Okwu said. “Come.”

“No,” I said. I retreated higher into the tree. And from there, I felt a clarity sharp as brittle crystal.

Okwu returned to me, as did Haifa and the Bear. The shuttle was stopping now. “Binti,” Okwu said, switching to Meduse. “Get up.”

“No.”

“It’s our stop,” Haifa said. “We have to get off. We’ve all got homework. And you know what the next stop is and that’s not even for another hour.”

“No,” I said, again. But even from the tree, my eyes welled up with tears. I gasped, wiped them away, but I didn’t move.

“Is she alright?” Haifa asked, turning to the Bear. The Bear moved to me, but she still said nothing. The closeness of her hairy body made my right arm feel warm.

“What . . . what are you doing?” I asked. I stared at her.

When she spoke, her voice was muffled because it came through layers of hair. “Red desert is next stop, Himba girl.”

“I know!” I said. And I said this from so deep in the tree that my voice must have resonated with it. Everyone getting off at the front of the shuttle stopped and turned to us.

“Okwu, move aside, I’ll pick her up,” Haifa screeched. “The shuttle’s going to leave soon!”

Haifa took only one step toward me before she stopped. The current I called up zinged an inch from the Bear’s hairs and both the Bear and Haifa moved back. We were the only ones left on the shuttle now. I held up my edan at Okwu, even if Okwu could withstand my current, my edan was poison to it. “I’m-not-getting-up,” I growled. All that was going through my mind at this point was one word over and over, “Go.” I needed to go. Away from my memories, away from my pain, away from my questions, go go go go go. I’d felt this only once in my life, back on the day I found my edan, when I felt my life was being controlled by everything but me. I’d wanted to dance and instead everyone else decided that I was not allowed.

“I’m going into the desert,” I said, more tears falling from my eyes. Pleading. “I have to go to the desert. I have to. I have to go.”

* * *

They stayed with me on the shuttle. My friends.

As it pulled off, I looked out the window and it was like I was leaving the planet. I watched us pass the Math City buildings and then our dorms. And then we were on our way, the only ones left on the shuttle. No one went to the red desert except those who were doing research and certainly not at this hour. And the final stop on this line was a small Oomza sterile swamp lab that was only active in the first morning because of the plants that used the evening time to digest everything in the area by the morning; no one went there at night, not even the shuttle, which stopped and returned an hour’s walk away from the swamp.

“Well, what are we going to do in the desert?” Haifa asked.

“You don’t have to do anything,” I said. “Just stay on the shuttle until it goes back.”

“We’re not leaving you there,” Okwu and Haifa said at the same time.

“You’re really going to do this?” Haifa asked.

“Yes.”

“You don’t have any water,” Okwu said.

I shrugged. Plus, I did have a capture station and a few mini apples in my satchel.

* * *

The shuttle stopped and in several alien languages including Meduse, some that vibrated and lit up the whole cab, it said, “Please exit the Shuttle.” I got off before it got to the three human languages. I walked down the walkway on legs that felt like warm rubber. What am I doing? I thought. But at the same time, it felt so good to do something, to get off the tracks. I paused, flaring my nostrils. One of those pitcher plants that secreted shuttle track oil that smelled like blood was growing on the other side of the tracks. I shuddered, pinching my nose and quickly moving down the red metal walkway. It ended where the sand began. I stopped, looking out at the desert. Behind us, the shuttle zipped away, gone in seconds. The silence it left us in was so complete that it was

like wearing noise-cancelling headgear. So much like home.

“This was not how I planned to spend my evening,” Haifa said, walking past me. She broke into a sprint, jumped with her arms stretched in the air and launched into a series of flips.

“This place has no water,” Okwu said, floating past me. “It is a dead place with no goddesses or gods and too many spirits.”

The Bear brushed swiftly past me, seeming to run after Haifa who was still doing flips and laughing. “Come, show me what you can do!” Haifa shouted and the Bear began to spin like a top, flinging sand everywhere. Haifa laughed harder, spreading her arms out and letting the sand the Bear flung up hit her squarely in the face, her eyes and mouth closed.

I turned from them all and started walking into the Oomza Red Desert of Umoya. When I had arrived on Oomza Uni, in that first week when I barely left my room, I’d obsessed over the hologram of the planet Oomza Uni on my astrolabe. I was acclimating myself. When I saw it with my own eyes on that day when Third Fish landed, after all that had happened, I’d wanted to know every detail about the planet.

This desert was not very big, but if you were human you could still die out here if you tried to cross it unprepared. If you didn’t die from the heat, then from the lack of water or the packs of roaming dog-like creatures the size of baby camels called cams, though you had to go in at least fifty miles to get to them.

I removed my sandals and dug my feet into the sand. It was just like home—cool and soft, but beneath the surface, it became warm like the flesh of a great beast. “Oh,” I sighed, closing my eyes. How I missed this. I called up a current and let it wash over my body like a second skin. Then I walked, bits of sand occasionally popping and sparking from my feet. The others followed.

We left the shuttle port behind. I left behind all the stares and gossiping, the People that knew I’d been on a ship where everyone had been killed and I’d been made genetically part of the killers. I left Professor Okpala behind. I left behind the fact that I was further from home that I had ever been. I kept walking.

Behind me, Okwu and Haifa bickered about whether they should grab me and risk getting zapped. The Bear’s hair near the bottom of her body grew full of sand and the sound of her gait got heavier and heavier. Oomza had one large moon and it was lit by the two suns, so the desert had plenty of white purple light. And because all deserts have a certain sameness, no matter the planet, I knew that after walking for what my astrolabe would have measured as a half earth hour, the land was about to change. My astrolabe would have shown this on its map, too, but I didn’t look at that. I didn’t want maps here.

Okwu floated up to me and said, “Remove your current.”

“No,” I said.

“We are here with you,” it said.

“We have no water, though,” Haifa said, walking a few yards away. “At least I don’t. These two will be fine out here, but you and I are gonna die.” I brought out my capture station and tossed it to her. “Oh!” Haifa said. “Well, at least I know you’re not completely suicidal.”

I kept walking.

* * *

I stopped walking when I came to a dead and dried bush.

We’d been walking for three hours and I stopped the moment I no longer felt like screaming. I let my current dissipate and then I sat down right there in the sand. “May the Seven keep me sane,” I whispered. And in that moment, they did. Haifa sat on the other side of the dried bush, facing me. The Bear, lowering herself beside her. Okwu hovered nearby me.

I threw my satchel to the side, glad to be rid of the weight. Despite the fact that Haifa had eaten most of my mini apples and was now carrying my capture station, my satchel seemed to have grown heavier by the minute as I’d walked. I looked at my arms, the desert air had dried the otjize on my skin and some of it was flaking off. I had been so focused on go go going that I hadn’t noticed.

I brought out the small washcloth I always carried and my jar of otjize.

“Are you alright now?” Okwu asked, hovering close behind me.

I slowly used the washcloth to rub off the dried otjize from my arms and then I’d get to my face. Back home, I’d never have done this in front of my parents, let alone my friends. “I’ve dragged you all out here,” I muttered. “Sorry.” I touched my okuoko and more otjize flaked off. I could see the blue of them beneath it in the bright moonlight. I frowned.

“A nice walk usually makes me feel better,” Haifa said. Then she laughed loudly and said, “Seriously, though, I hope we don’t die out here.” She laughed again.

“That would not be a respectable death,” Okwu said.

I flaked more otjize off my okuoko. My left eye twitched and I grabbed one of my okuoko. It hurt. “Okwu,” I said. “Why’d you do this to me?” I turned to it. I waited, breathing heavily. In the light of the moon, the smoothness of its blue dome perfectly reflected the sand.

“Our chief demanded it,” Okwu said.

“But it’s my body,” I screamed at it. “I went into the Meduse ship for peace. Your people, you all just . . . why couldn’t you have just asked?! Let . . . let me choose?!”

“Not everything can be a choice.”

Five five five five five five. I calmed. I could see it even in the ripples of the sand. Back home, I’d been born able to tree and I’d been born with the skill to call up current, to harmonize. When I honed that skill, it bloomed with ease and joy because I was moving in the direction of the Seven. And so my family, my people decided my fate. Or so they thought.

I got up, my legs shaking. I stared at the dried bush. I broke the number sixty-four in half, broke it again, then again, then again as I called up a current. I held up my left hand, letting the current circulate in my palm like a tiny burning planet. Then I whipped my hand toward the dried bush and let it shoot right into its center. Crack!

“Binti!” Haifa exclaimed, jumping back as the bush burst into flame, lighting the desert around us. Okwu moved away, too. Not far behind Okwu, I saw something skitter away.

“Back home, the Himba view the okuruwo as the gateway to the Seven,” I said, as the fire grew. The warmth it gave off was nice in the cooling desert air. “Okuruwo means ‘sacred fire’ in my language. The council elders keep it burning so that we are always connected to the Seven. Heat, fire, smoke, it all leads to the Seven.” I stepped a few feet to my right so that I was in the path of the smoke as the breeze blew. I let the smoke wash over me. “Centuries ago, Himba women would take smoke baths because they believed it cleaned them more deeply than water,” I said. Yet it’s unbreathable, like Okwu’s gas, I thought.

I brought out my edan and held it in my bandaged hand. I glared at it, the smoke obscuring me from the others for the moment as the desert night breeze blew. I touched the many points of its stellated cube form. It had saved my life and built a bridge of communication between myself and a prideful murderous tribe and I still didn’t know what it was. If I hadn’t found it in the desert back when I was eight years old, would I still be home?

A tiny bit of blood had seeped through my bandage, a tiny red flower. Like the red flower on Heru’s chest. Instead of casting the thing into the fire, I opened my mouth and inhaled the fire’s smoke. My chest felt as if I’d lit it afire and I coughed violently.

“Eeeeeeeeee!!”

I jumped, still coughing, unconsciously putting my edan in my pocket. Okwu, who’d been beside me, suddenly was not. I whirled around. Something near the fire was exploding! Haifa was jumping in the flames and tackling it.

The Bear had caught fire! I ran to Haifa who was rolling the Bear this way and that, trying to put out the Bear’s hair. “Throw sand! Throw sand!” I shouted. Okwu started whirling around like a top. I’d never seen it do that. Its whirling sprayed the Bear with copious amounts of sand. I scuttled about throwing sand, too. And all through, the Bear continued shrieking, “Eeeeeeeeeeeeee!”

When the fire was out, the Bear was left with a large patch of her hair burned away, revealing a bald spot of black flesh just above one of her thick legs. I saw that the Bear actually had three thick stumpy brown legs, which explained how she moved so agilely.

I lay on the sand beside the Bear as she sighed softly. Haifa lay where the Bear’s chest would have been had she had a chest. Okwu hovered beside us. “Fire can be an evil spirit,” it said.

“Why’d you have to get so close?” Haifa breathed, looking angrily at the Bear.

“Fire’s the gateway to the Seven,” I said, staring at the sky.

“It beautiful,” the Bear said.

“You should privilege life before beauty,” Okwu said.

I rolled my eyes.

* * *

The Bear was okay. It turned out that within an hour, her hair began to grow back over the bald spot and the burned flesh, though still tender, was already healing. Her kind of People were hearty. I realized that her foolish behavior wasn’t as perilous as it looked, just painful and a bit embarrassing. Even more fascinating, in a pouch near her chest, the Bear carried a sheer cloth-like thing that she could stretch into a large tent. The Bear was of a nomadic people who could sleep anywhere in comfort. With the items in my satchel and dragging my friends along, I’d come far more prepared for a night in one of Oomza Uni’s deserts than I could have ever imagined.

It took the Bear minutes to set up what I could only call . . . a flesh tent. It wasn’t part of her flesh, but it was made of her flesh, at least according to Haifa. The Bear placed the small square on the ground. It might have been a light purple, but in the firelight this was difficult to tell. The Bear stepped on the square and began to tap at different spots on it with her several toes. With each tap, a part of it unfolded and unfurled like the wings of a butterfly, until eventually the Bear stepped back and it was as if the thing had a life of its own . . . and really did become a delicate creature not so unlike a butterfly.

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade

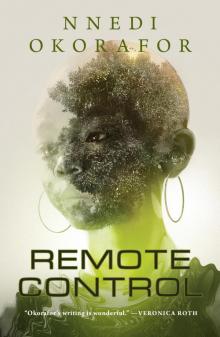

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Remote Control

Remote Control Binti: The Night Masquerade

Binti: The Night Masquerade Binti--The Night Masquerade

Binti--The Night Masquerade Kabu Kabu

Kabu Kabu Binti

Binti Zahrah the Windseeker

Zahrah the Windseeker Akata Witch: A Novel

Akata Witch: A Novel Ikenga

Ikenga Who Fears Death

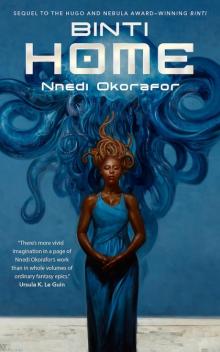

Who Fears Death Binti--Home

Binti--Home Lagoon

Lagoon Akata Witch

Akata Witch The Book of Phoenix

The Book of Phoenix Akata Warrior

Akata Warrior Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi

Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi