- Home

- Nnedi Okorafor

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Page 6

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Read online

Page 6

“Let them do the right thing,” the chief said.

Feet away from us, beyond the glass table, these professors were shouting with anger, sometimes guffawing with glee, flicking antennae in each other’s faces, making ear-popping clicks to get the attention of colleagues. One professor, about the size of my head, flew from one part of the group to the other, producing webs of gray light that slowly descended on the group. This chaotic method of madness would decide whether I would live or die.

I caught bits and pieces of the discussion about Meduse history and methods, the mechanics of the Third Fish, the scholars who’d brought the stinger. Okwu and the chief didn’t seem to mind hovering there waiting. However, my legs soon grew tired and I sat down right there on the blue floor.

* * *

Finally, the professors quieted and took their places at the glass table again. I stood up, my heart seeming to pound in my mouth, my palms sweaty. I glanced at the chief and felt even more nervous; its okuoko were vibrating and its blue color was deeper, almost glowing. When I looked at Okwu, where its okuoko hung, I caught a glimpse of the white of its stinger, ready to strike.

The spiderlike Haras raised two front legs and spoke in the language of the Meduse and said, “On behalf of all the people of Oomza Uni and on behalf of Oomza University, I apologize for the actions of a group of our own in taking the stinger from you, Chief Meduse. The scholars who did this will be found, expelled, and exiled. Museum specimen of such prestige are highly prized at our university, however such things must only be acquired with permission from the people to whom they belong. Oomza protocol is based on honor, respect, wisdom, and knowledge. We will return it to you immediately.”

My legs grew weak and before I knew it, I was sitting back on the floor. My head felt heavy and tingly, my thoughts scattered. “I’m sorry,” I said, in the language I’d spoken all my life. I felt something press my back, steadying me. Okwu.

“I am all right,” I said, pushing my hands to the floor and standing back up. But Okwu kept a tentacle to my back.

The one named Haras continued. “Binti, you have made your people proud and I’d personally like to welcome you to Oomza Uni.” It motioned one of its limbs toward the human woman beside it. She looked Khoush and wore tight-fitting green garments that clasped every part of her body, from neck to toe. “This is Okpala. She is in our mathematics department. When you are settled, aside from taking classes with her, you will study your edan with her. According to Okpala, what you did is impossible.”

I opened my mouth to speak, but Okpala put up a hand and I shut my mouth.

“We have one request,” Haras said. “We of Oomza Uni wish Okwu to stay behind as the first Meduse student to attend the university and as a showing of allegiance between Oomza Uni governments and the Meduse and a renewal of the pact between human and Meduse.”

I heard Okwu rumble behind me, then the chief was speaking up. “For the first time in my own lifetime, I am learning something completely outside of core beliefs,” the chief said. “Who’d have thought that a place harboring human beings could carry such honor and foresight.” It paused and then said, “I will confer with my advisors before I make my decision.”

The chief was pleased. I could hear it in its voice. I looked around me. No one from my tribe. At once, I felt both part of something historic and very alone. Would my family even comprehend it all when I explained it to them? Or would they just fixate on the fact that I’d almost died, was now too far to return home and had left them in order to make the “biggest mistake of my life”?

I swayed on my feet, a smile on my face.

“Binti,” the one named Okpala said. “What will you do now?”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “I want to study mathematics and currents. Maybe create a new type of astrolabe. The edan, I want to study that and . . .”

“Yes,” she said. “That is true, but what about your home? Will you ever return?”

“Of course,” I said. “Eventually, I will visit and . . .”

“I have studied your people,” she said. “They don’t like outsiders.”

“I’m not an outsider,” I said, with a twinge of irritation. “I am . . .” And that’s when it caught my eye. My hair was rested against my back, weighed down by the otjize, but as I’d gotten up, one lock had come to rest on my shoulder. I felt it rub against the front of my shoulder and I saw it now.

I frowned, not wanting to move. Before the realization hit me, I knew to drop into meditation, treeing out of desperation. I held myself in there for a moment, equations flying through my mind, like wind and sand. Around me, I heard movement and, still treeing, I saw that the soldiers were leaving the room. The professors were getting up, talking among themselves in their various ways. All except Okpala. She was looking right at me.

I slowly lifted up one of my locks and brought it forward I rubbed off the ojtize. It glowed a strong deep blue like the sky back on earth on a clear day, like Okwu and so many of the other Meduse, like the uniforms of the Oomza Uni soldiers. And it was translucent. Soft, but tough. I touched the top of my head and pressed. They felt the same and . . . I felt my hand touching them. The tingling sensation was gone. My hair was no longer hair. There was a ringing in my ear as I began to breathe heavily, still in meditation. I wanted to tear off my clothes and inspect every part of my body. To see what else that sting had changed. It had not been a sting. A sting would have torn out my insides, as it did for Heru.

“Only those,” Okwu said. “Nothing else.”

“This is why I understand you?” I flatly asked. Talking while in meditation was like softly whispering from a hole deep in the ground. I was looking up from a cool dark place.

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because you had to understand us and it was the only way,” Okwu said.

“And you needed to prove to them that you were truly our ambassador, not prisoner,” the chief said. It paused. “I will return to the ship; we will make our decision about Okwu.” It turned to leave and then turned back. “Binti, you will forever hold the highest honor among the Meduse. My destiny is stronger for leading me to you.” Then it left.

I stood there, in my strange body. If I hadn’t been deep in meditation I would have screamed and screamed. I was so far from home.

* * *

I’m told that news of what had happened spread across all Oomza Uni within minutes. It was said that a human tribal female from a distant blue planet saved the university from Meduse terrorists by sacrificing her blood and using her unique gift of mathematical harmony and ancestral magic. “Tribal”: that’s what they called humans from ethnic groups too remote and “uncivilized” to regularly send students to attend Oomza Uni.

Over the next two days, I learned that people viewed my reddened dark skin and strange hair with wonder. And when they saw me with Okwu, they grew tense and quiet, moving away. Where they saw me as a fascinating exotic human, they saw Okwu as a dangerous threat. Okwu was of a warlike people who, up until now, had only been viewed with fear among people from all over. Okwu enjoyed its infamy, whereas I just wanted to find a quiet desert to walk into so I could study in peace.

“All people fear decisive, proud honor,” Okwu proclaimed.

We were in one of the Weapons City libraries, staring at the empty chamber where the chief’s stinger had been kept. A three-hour transport from Math City, Weapons City was packed with activity on every street and crowded with sprawling flat gray buildings made of stone. Beneath each of these structures were inverted buildings that extended at least a half-mile underground where only those students, researchers, and professors involved knew what was being invented, tested, or destroyed. After the meeting, this was where they’d taken me, the chief, and Okwu for the retrieval of the stinger.

We’d been escorted by a person who looked like a small green child with roots for a h

ead, who I later learned was the head professor of Weapons City. He was the one who went into the five-by-five-foot case made of thick clear crystal and opened it. The stinger was placed atop a slab of crystal and looked like a sharp tusk of ice.

The chief slowly approached the case, extended an okuoko, and then let out a large bluish puff of gas the moment its okuoko touched the stinger. I’ll never forget the way the chief’s body went from blue to clear the moment the stinger became a part of it again. Only a blue line remained at the point of demarcation where it had reattached—a scar that would always remind it of what human beings of Oomza Uni had done to it for the sake of research and academics.

Afterward, just before the chief and the others boarded the Third Fish that would take them back to their own ship just outside the atmosphere, upon Okwu’s request, I knelt before the chief and placed its stinger on my lap. It was heavy and it felt like a slab of solid water and the edge at its tip looked like it could slice into another universe. I smeared a dollop of my otjize on the blue scar where it had reattached. After a minute, I wiped some of it away. The blue scar was gone. Their chief was returned to its full royal translucence, they had the half jar of otjize Okwu had taken from me, which healed their flesh like magic, and they were leaving one of their own as the first Meduse to study at the great Oomza University. The Meduse left Oomza Uni happier and better off than when they’d arrived.

* * *

My otjize. Yes, there is a story there. Weeks later, after I’d started classes and people had finally started to leave me be, opting to simply stare and gossip in silence instead, I ran out of otjize. For days, I’d known it would happen. I’d found a sweet-smelling oil of the same chemical makeup in the market. A black flower that grew in a series of nearby caverns produced the oil. But a similar clay was much harder to find. There was a forest not far from my dorm, across the busy streets, just beyond one of the classroom buildings. I’d never seen anyone go into it, but there was a path opening.

That evening, before dark, I walked in there. I walked fast, ignoring all the stares and grateful when the presence of people tapered off the closer I got to the path entrance. I carried my satchel with my astrolabe, a bag of nuts, my edan in my hands, cool and small. I squeezed my edan as I left the road and stepped onto the path. The forest seemed to swallow me within a few steps and I could no longer see the purpling sky. My skin felt near naked, the layer of otjize I wore was so thin.

I frowned, hesitating for a moment. We didn’t have such places where I came from and the denseness of the trees, all the leaves, the small buzzing creatures, made me feel like the forest was choking me. But then I looked at the ground. I looked right there, at my sandaled feet and found precisely what I needed.

I made the otjize that night. I mixed it and then let it sit in the strong sunshine for the next day. I didn’t go to class, nor did I eat that day. In the evening, I went to the dorm and showered and did that which my people rarely do: I washed with water. As I let the water run through my hair and down my face, I wept. This was all I had left of my homeland and it was being washed into the runnels that would feed the trees outside my dorm.

When I finished, I stood there, away from the running stream of water that flowed from the ceiling. Slowly, I reached up. I touched my “hair.” The okuoko were soft but firm and slippery with wetness. They touched my back, soft and slick. I shook them, feeling them otjize-free for the first time.

I shut my eyes and prayed to the Seven; I hadn’t done this since arriving on the planet. I prayed to my living parents and ancestors. I opened my eyes. It was time to call home. Soon.

I peeked out of the washing space. I shared the space with five other human students. One of them just happened to be leaving as I peeked out. As soon as he was gone, I grabbed my wrapper and came out. I wrapped it around my waist and I looked at myself in the large mirror. I looked for a very very long time. Not at my dark brown skin, but where my hair had been. The okuoko were a soft transparent blue with darker blue dots at their tips. They grew out of my head as if they’d been doing that all my life, so natural looking that I couldn’t say they were ugly. They were just a little longer than my hair had been, hanging just past my backside, and they were thick as sizable snakes.

There were ten of them and I could no longer braid them into my family’s code pattern as I had done with my own hair. I pinched one and felt the pressure. Would they grow like hair? Were they hair? I could ask Okwu, but I wasn’t ready to ask it anything. Not yet. I quickly ran to my room and sat in the sun and let them dry.

Ten hours later, when dark finally fell, it was time. I’d bought the container at the market; it was made from the shed exoskeleton of students who sold them for spending money. It was clear like one of Okwu’s tentacles and dyed red. I’d packed it with the fresh otjize, which now looked thick and ready.

I pressed my right index and middle finger together and was about to dig out the first dollop when I hesitated, suddenly incredibly unsure. What if my fingers passed right through it like liquid soap? What if what I’d harvested from the forest wasn’t clay at all? What if it was hard like stone?

I pulled my hand away and took a deep breath. If I couldn’t make otjize here, then I’d have to . . . change. I touched one of my tentacle-like locks and felt a painful pressure in my chest as my mind tried to take me to a place I wasn’t ready to go to. I plunged my two fingers into my new concoction . . . and scooped it up. I spread it on my flesh. Then I wept.

* * *

I went to see Okwu in its dorm. I was still unsure what to call those who lived in this large gas-filled spherical complex. When you entered, it was just one great space where plants grew on the walls and hung from the ceiling. There were no individual rooms, and people who looked like Okwu in some ways but different in others walked across the expansive floor, up the walls, on the ceiling. Somehow, when I came to the front entrance, Okwu would always come within the next few minutes. It would always emit a large plume of gas as it readjusted to the air outside.

“You look well,” it said, as we moved down the walkway. We both loved the walkway because of the winds the warm clear seawater created as it rushed by below.

I smiled. “I feel well.”

“When did you make it?”

“Over the last two suns,” I said.

“I’m glad,” it said. “You were beginning to fade.”

It held up an okuoko. “I was working with a yellow current to use in one of my classmate’s body tech,” it said.

“Oh,” I said, looking at its burned flesh.

We paused, looking down at the rushing waters. The relief I’d felt at the naturalness, the trueness of the otjize immediately started waning. This was the real test. I rubbed some otjize from my arm and then took Okwu’s okuoko in my hand. I applied the otjize and then let the okuoko drop as I held my breath. We walked back to my dorm. My otjize from Earth had healed Okwu and then the chief. It would heal many others. The otjize created by my people, mixed with my homeland. This was the foundation of the Meduse’s respect for me. Now all of it was gone. I was someone else. Not even fully Himba anymore. What would Okwu think of me now?

When we got to my dorm, we stopped.

“I know what you are thinking,” Okwu said.

“I know you Meduse,” I said. “You’re people of honor, but you’re firm and rigid. And traditional.” I felt sorrow wash over and I sobbed, covering my face with my hand. Feeling my otjize smear beneath it. “But you’ve become my friend,” I said. When I brought my hand away, my palm was red with otjize. “You are all I have here. I don’t know how it happened, but you are . . .”

“You will call your family and have them,” Okwu said.

I frowned and stepped away from Okwu. “So callous,” I whispered.

“Binti,” Okwu said. It exhaled out gas, in what I knew was a laugh. “Whether you carry the substance that can heal and bring li

fe back to my people or not, I am your friend. I am honored to know you.” It shook its okuoko, making one of them vibrate. I yelped when I felt the vibration in one of mine.

“What is that?” I shouted, holding up my hands.

“It means we are family through battle,” it said. “You are the first to join our family in this way in a long time. We do not like humans.”

I smiled.

He held up an okuoko. “Show it to me tomorrow,” I said, doubtfully.

“Tomorrow will be the same,” it said.

When I rubbed off the otjize the burn was gone.

* * *

I sat in the silence of my room looking at my edan as I sent out a signal to my family with my astrolabe. Outside was dark and I looked into the sky, at the stars, knowing the pink one was home. The first to answer was my mother.

The fact that the bridge is shaky does not mean it will break.

—an Enyi Zinariya proverb

I even missed my sisters.

And it wasn’t just because it was one of those nights. You see, there’s something that happens to a child of the soil when she leaves her soil. It’s a death, then a painful rebirth . . . but first you have to walk around the new world as a sort of ghost. I was a ghost at Oomza Uni. Displaced but still in the place I needed to be. The place where I wanted to be. If only people understood that. Understood me.

And I even missed my sisters.

I squatted there in the dirt. This place beside my dorm was a favorite spot of mine because the soil here was dry like back home. There was also a flat green sturdy plant that grew in a crack at the edge of the dorm building’s wall. It grew in fives, five leaves on five branches in bunches of five. And the plant smelled nice at this time of day. My mother would have loved these plants as much as I did and my father would have wanted to study them and see if their leaves conducted current. They didn’t; I’d tried running a current through them already. Nothing. But the plants knew mathematics, which was even godlier. Praise the Seven for these plants of the fives, my new favorite number.

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Remote Control

Remote Control Binti: The Night Masquerade

Binti: The Night Masquerade Binti--The Night Masquerade

Binti--The Night Masquerade Kabu Kabu

Kabu Kabu Binti

Binti Zahrah the Windseeker

Zahrah the Windseeker Akata Witch: A Novel

Akata Witch: A Novel Ikenga

Ikenga Who Fears Death

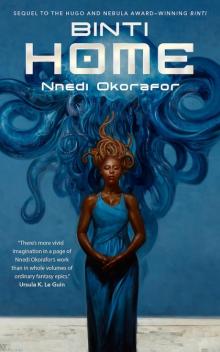

Who Fears Death Binti--Home

Binti--Home Lagoon

Lagoon Akata Witch

Akata Witch The Book of Phoenix

The Book of Phoenix Akata Warrior

Akata Warrior Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi

Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi