- Home

- Nnedi Okorafor

Ikenga Page 5

Ikenga Read online

Page 5

“I know.”

She paused, again. Nnamdi bristled, sure that she was going to start badgering him about what had happened last night or about the Ikenga.

“Why do your fingers look like that?” Chioma asked.

“Like what?” he asked, looking at his hands.

“Dirty.”

“Oh.” He laughed, picking at them. “I’ve been . . . I’ve been working in my father’s garden.”

They both paused.

“Have the butterflies returned?” she asked quietly.

Nnamdi shook his head. In all his time weeding, watering, planting, and pruning back there, he hadn’t seen one butterfly. He hadn’t really thought much of this until Chioma pointed it out. Now it made his heart ache.

Chioma got up. “Let’s go find Ruff Diamond. I want to hear his take on the Three Days’ Journey incident.” She giggled.

“Mmmm, okay.” Nnamdi liked Ruff Diamond well enough, but he didn’t quite trust him because of how much Ruff Diamond loved to exaggerate and embellish everything. He’d be stung by a fly, but when he told you about it, the fly would turn into some enormous, rare blue bumblebee. Or he’d always just happened to be a block away from big things that happened. Nnamdi didn’t care for his wide mouth, but Chioma always enjoyed his nonsense regardless of how little of it was true. They found Ruff Diamond chatting with a group of boys outside a clothing shop. Ruff Diamond waved and came right over when he saw them.

“You caught me just before I have to leave again,” Ruff Diamond said.

“What do you mean? Your mother is back already?” Chioma asked. “But you were just at her house!”

“Yep. I hear my parents had a big fight, again. One day I’m there, then the next I’m here,” he said with a lopsided smile. “That’s divorce, I guess. Two big homes, two schools.”

“Oh, poor you,” Chioma said, rolling her eyes.

“Nah, I’m rich, not poor,” Ruff Diamond said, smirking.

Nnamdi bristled so hard that his armpits prickled. Ruff Diamond was so annoying. “Well, you didn’t miss much,” he muttered.

“Ha ha, you’re funny, man,” Ruff Diamond said. “But you’re right. I almost stepped directly into the trouble. We got home last night probably at the same time Three Days’ Journey was attacking,” he said as they walked into school. “We were probably a few houses away, about to reach home. My mom was driving the black Jaguar. I’ll bet Three Days’ Journey would have attacked us if he saw our car first.”

“It happened near my house,” Nnamdi said. “You live fifteen minutes away.”

“All I’m saying is that we were lucky last night,” Ruff Diamond insisted, annoyed.

“Nnamdi’s the one who’s lucky,” Chioma said. “He was out there, probably less than a block from where it happened, as it was happening!”

“Did you see anything?” Ruff Diamond asked, cocking his head.

“I think he did,” Chioma said.

“Chioma,” Nnamdi groaned.

“Well, what’d you see?” Ruff Diamond pressed.

“Nothing,” Nnamdi said. Chioma opened her mouth to say something, but when Nnamdi met her eyes, she instantly shut her mouth, frowning. Good, he thought. Glad she can be quiet sometimes. He felt a pinch of guilt; he didn’t like the look on her face. She almost looked scared.

“Well, if you did, I’ll bet you could make a lot of money telling the press,” Ruff Diamond said. “They’d pay even a kid for information, I think.”

Chioma was still looking at him.

“I didn’t see anything,” Nnamdi insisted. “It was dark. A lot of people were out last night.”

Bad Market

AFTER SCHOOL, NNAMDI and Chioma walked home along the busy street. Cars zoomed by. Banana and bread hawkers screamed their wares, their large trays balanced on their heads. Auto mechanics cooled off beneath mango trees, drinking cold water from small plastic bags. It was a breezy afternoon and Nnamdi felt so good that for a moment he forgot about the night before. Then he made eye contact with a tired-looking woman selling bread and he thought of his mother selling tapioca. He felt terrible and . . . guilty. His mother would be returning from the market about now, alone and unprotected, and here he was having a fun walk home with a friend.

And if the newspapers would pay him for information about last night, what would be so crazy about going and telling them something? He could give every naira to his mother. That would be less time she spent selling tapioca at the market.

He could always say that he saw a shadowy man attack Three Days’ Journey and save the woman. Technically, he wouldn’t be lying. He’d seen his dark hands. But then, when the paper was published, he’d get more questions from Chioma and his mother. He’d get more questions from everyone. And then, at some point, he knew he’d have to start lying. It wasn’t worth the risk.

“Let’s go see if we can find my mother,” Nnamdi said.

“At the market?” Chioma asked.

“I want to make sure she’s . . . okay,” he said.

Chioma nodded and he was glad. He didn’t want to do any more explaining.

When they got to the market, they didn’t have to look hard. There she was, walking past the booths and tables with her tray of tapioca on her head. Nnamdi felt another pinch of guilt. No one would have believed his mother could sink so low. She used to be the wife of the chief of police. People like her didn’t have to work. People like her kept many of the market women in business by buying what they sold.

Nnamdi watched from a distance as his mother walked. People stopped and stared. Even a year later, people here still hadn’t gotten used to seeing her as one of them. She must have felt it. Nnamdi certainly did. Shame. Again he thought about the money he could get from the newspapers . . . and he thought of the Chief of Chiefs, who’d caused all this.

“Mommy,” he called, waving his hand. He and Chioma ran to her.

She smiled wanly. The armpits of her yellow blouse were damp with sweat and her feet were caked with dust. She walked slowly, wincing with each step. Nnamdi cringed. His mother had terrible bunions on both feet.

“Good afternoon, Mrs. Icheteka,” Chioma said.

“Good afternoon, Nnamdi, Chioma,” she said as Nnamdi quickly took her tray. “Thank you, Nnamdi.” She stretched her back and Nnamdi could hear her joints pop.

“Mommy, you can’t do this anymore. You look—”

“How was school?” his mother asked, cutting him off.

“Okay,” he mumbled. She put her arms around both of their shoulders and they started walking home together.

They’d walked past several market stalls when Nnamdi smelled something utterly rotten. It was so rancid that he swooned with dizziness and nearly dropped the tray. The air itself took on a noxious green tint, like stinky fog. The stench was thickest in the market, tumbling out from between the stalls.

“Phew! What is that?” Chioma exclaimed, pinching her nose. “Oh my God! Nasty!”

His mother grabbed Nnamdi’s arm and, when he looked at her, he knew they were thinking the same thing. She was the chief’s wife and he was the chief’s son. They both knew exactly what was happening and who had caused it. Then Nnamdi remembered the Ikenga . . . and what it could do.

“Chioma,” Nnamdi said. He wriggled his hand from his mother’s grasp. “Take this.” He shoved the tapioca tray into her arms. “Stay with my mother! Please.”

“No problem,” she said, her voice sounding nasal because she was pinching her nose. “You’re not going in there, are you?!”

“Nnamdi!” his mother snapped, trying to grab his arm again. “Where are you going?”

“I . . . I just want to go see,” he said, stepping away. He’d never been a very good liar.

“Where . . . what are you going to do?” Chioma asked.

“Just stay with my mother!” he said.

>

“Nnamdi!” his mother screeched in a voice that made Nnamdi cringe. “Where are you going?”

Nnamdi ran into the green fog.

* * *

He coughed and leaned forward, putting his hands on his knees. Everything was stinky green haze. He could barely see three feet in front of him. However, he could hear people stumbling about and coughing.

“Bad Market,” he whispered. That was who was behind this. Nnamdi remembered his father’s description perfectly: “Bad Market is the head of a small but very crafty group of pickpockets,” Nnamdi’s father had explained to him only months before his murder. “When Bad Market finishes a job, he gets arrogant. He likes people to know they’ve been robbed; that’s part of the thrill for him. He has these balloons filled with chemicals. He throws them when he is done robbing, and when they hit the air, that creates the smelly fog he is known for.”

Nnamdi’s father had said that Bad Market was a tall man who looked like a fashion model. He was light on his feet and therefore able to outrun authorities in all the confusion.

“Light on his feet,” Nnamdi whispered. “Think. Gotta think.” Nnamdi took a deep breath and relaxed his shoulders. What’s my task? What’s my task? What’s my task? he thought. What do I need to do? He whispered, closing his eyes, “Find Bad Market.” There was a brief pause in which he heard a fly buzz past his ear and a car honk its horn from nearby, then he felt himself . . . shift.

A coolness settled on his shoulders. His body felt as if it moved to the left, just a tiny bit. Then his senses opened up. He felt his nostrils expand and the terrible smell grew so full that it was like an actual taste on his tongue. And he felt his ears expand and suddenly he could hear everything. People bickering about whether to run or hide, babbling in fear, or shouting angrily as they discovered that their jewelry, shopping, and money were gone. He honed in on the sound of feet. Little feet. Children running. He strained harder. There. Bigger feet.

“That’s Bad Market,” he said out loud. He gasped. His voice was so low. He opened his eyes. At first, all he saw was green. Then, as his powerful eyes adjusted, he began to see more. A woman was on her knees, feeling around for whatever she’d lost. A child to his right was standing there, crying. Nnamdi wanted to help, but he knew the best way to help was to focus. As he worked to do so, he looked down at his body. “Oh God,” he whispered. He was a piece of outer space in the shape of a man. “What is . . . Wow.” He pressed at his arm; it felt like an arm but looked like blackness blending into blackness.

Focus, he thought again. He shut his eyes. To kill the snake, you cut off its head. It was what his mother was fond of saying when she talked about how she felt one should fight Kaleria’s crime. Nnamdi had never understood it and he still didn’t. But the idea was fierce and it gave him strength. Focus. Slowly, the noise of chaos fell away and his ears pinpointed the sound of swift, nimble adult feet. Without opening his eyes, he took off in pursuit.

He was like a bat using sonar, seeing with sound. Eyes closed as he ran, all he had to do was listen. He ran past people and around corners and market stall dividers. He leapt over a dog. He didn’t lose the sound of the swift footsteps. They were running faster now but also growing louder. Bad Market was fast, but Nnamdi was faster. He was closing in. Closer. Closer . . .

Nnamdi opened his eyes just in time to see the back of Bad Market’s suit jacket and sacks full of stolen items over his shoulders. Through the stench of the green fog, Nnamdi could smell Bad Market’s designer cologne. He moved closer, reached out, and then grabbed him. They both went tumbling. The sacks of stolen naira, watches, rings, and necklaces went flying and fell onto a pile of firewood.

Bad Market tried to roll from beneath him, but Nnamdi was too big. Nnamdi snatched up Bad Market’s arms and held them together as the limber man tried to squirm from his grasp. Nnamdi was so strong that he was able to drag the kicking and twisting Bad Market and lift him off the ground.

He held Bad Market up to his face. Nnamdi remembered his father describing Bad Market as tall, about six two. However, Nnamdi was a giant, standing probably a foot taller. Bad Market flailed about for a moment, then he looked into Nnamdi’s face and screamed wildly. Then he . . . fainted. After all the thrashing and shrieking, the sudden silence was almost ridiculous to Nnamdi. He frowned and inspected Bad Market, then he dropped him with disgust. What kind of grown man faints? Nnamdi wondered. But then again, what kind of “man” did he look like?

The smelly green fog was dissipating and, though they were in a secluded section of the open-air market, Nnamdi sensed people nearby. What could he do? Tie up Bad Market, he decided, and get out of there before anyone saw him. He was looking around for something to use when Bad Market suddenly leapt up, grabbed a log of firewood, and smashed it against the side of Nnamdi’s head. “YAH!” Bad Market shouted triumphantly.

Nnamdi stumbled backward, blinking and shaking his head. Bad Market was taller than his father, but very lean. He was dressed like the men Nnamdi saw on billboards and his face was twisted as he raised the log to beat Nnamdi some more. On instinct, Nnamdi caught the other end of the log with one hand and slapped Bad Market hard across the face with his other. Bad Market flew back as fast and powerfully as a kicked football. When he landed, he didn’t move. “Oh no,” Nnamdi whispered. He crept up to Bad Market’s limp body and nudged him with his shadowy foot. Bad Market still didn’t move. He nudged harder. Nothing. Quickly, the fog was disappearing and he saw four or five people standing there, staring.

“This is Bad Market,” Nnamdi announced. He fought back the embarrassed giddiness he felt at his rich, deep voice. They don’t know, he assured himself. They just see a big shadow man. He straightened up so that he stood much taller than he felt, and looked at an old woman, who whimpered and stepped back. Three men stood there but made no move to help. Oh God, Nnamdi thought. I hope he’s not dead. He paused. Then he finally knelt down and shoved Bad Market onto his back. Bad Market rolled over, his eyes closed and mouth hanging open as it let out a loud snore. Nnamdi sighed with relief. He was just sleeping. Someone tapped Nnamdi on the arm. When he looked to the side, he saw the old woman.

“Here, take this,” she said, handing him a scarf, scowling at him with narrowed eyes. She crept back, her eyes still on him. There had to be ten people around him now. All seeing him. He suddenly felt cold. Then he felt as if all his muscles were relaxing. He was changing back. Quickly, he tied Bad Market’s limp hands with the scarf. Then he ran off.

* * *

Nnamdi breathed heavily as he fled. He felt the shadow self slipping from him and the feeling left him light-headed, as if he’d been hanging upside down. He rushed behind a house and sat down hard with his back against the wall. He could feel it; he was not himself yet. He could feel the length of his legs and arms. He could see his flesh, black like outer space in a Star Wars movie. However, his muscles felt mushy and weak. He wheezed and coughed. Suddenly, a force lifted him off the ground and slammed him to the floor. “Ooof!” he grunted, the little air in his lungs knocked out. As he lay there in the dirt, he wondered what would happen next. Was this his father? Was the power that had been controlling him going wrong? He’d hurt Three Days’ Journey, too. Was God punishing him for harming yet another person? He pressed the heels of his palms to his eyes, trying to shake away the image of Bad Market flying back fast and hard because of Nnamdi’s slap. Nnamdi had never slapped anyone in his life. God would punish him for sure.

When nothing more happened, he coughed again and slowly pulled himself upright. He leaned his head against the wall and looked down at his school clothes. Filthy. At least the shadow hadn’t eaten them away. Still, his mother was going to be so angry. He gasped. He had to get back to his mother and Chioma. They were probably still outside the market, worrying about where he’d gone.

He was about to get up when he heard soft chuckling. He froze, his mouth hanging open. It sounded like it wa

s right beside him. But there was nothing there. “It’s okay, son. Be more careful,” he heard his father say. Nnamdi tensed up, his eyes wide. Then he heard his father’s laughter, low and musical. Nnamdi listened as it faded into the distance. As if . . . as if his father were walking away.

“I won’t hurt anyone again,” Nnamdi said to the space around him. Only a brown goat tethered to a pole nearby responded. “Baaaah.”

A peacefulness spread over Nnamdi and he changed completely back to himself and collapsed onto the dirt, overcome with a pounding headache and deep fatigue. This time he didn’t pass out. With lidded eyes, he stared at his now small shaky dark-brown-skinned hands.

“No,” he said to himself. “I won’t hurt another person.”

* * *

“Oh, thank God!” Chioma exclaimed when Nnamdi found them.

Once the smelly green fog had cleared, Nnamdi’s mother and Chioma had walked all over the market, looking for him. They told him how they saw people who’d fallen or bumped into each other or tumbled over things in the heavy fog. They’d seen people standing in line as police gave them back their things. And, like everyone in the area, they’d witnessed the capture of Bad Market.

“You missed all the excitement!” Chioma said. “Well, so did we, but we got to see the police shove Bad Market into a police car. He’s really good-looking.”

Nnamdi rolled his eyes. Chioma was always pointing out “good-looking” men.

“I wish they would catch Never Die,” his mother growled, and Nnamdi knew she was remembering how he’d robbed her on her way home from the market. “So, what happened to you in there?”

“I guess I kind of just got lost in the fog,” he said with a laugh that sounded false even to him. He avoided Chioma’s suspicious eyes.

* * *

That night, as soon as he hit the bed, Nnamdi fell fast asleep. But again it wasn’t a peaceful sleep. For what felt like hours, he was chased by the shadowy grotesque demon version of Three Days’ Journey, who seemed to be made of a sticky brown goop that stained everything it touched. And always present was the glowing Ikenga, now the size of his father, floating after him and pointing its machete.

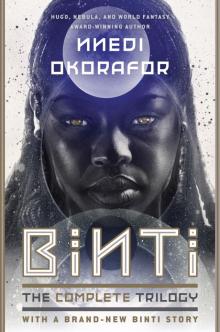

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade

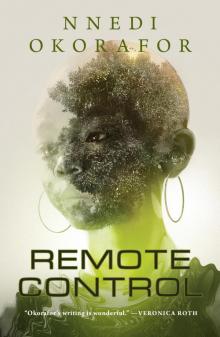

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Remote Control

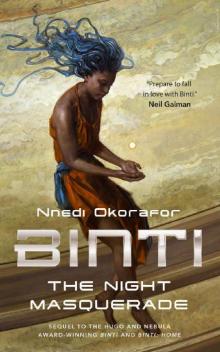

Remote Control Binti: The Night Masquerade

Binti: The Night Masquerade Binti--The Night Masquerade

Binti--The Night Masquerade Kabu Kabu

Kabu Kabu Binti

Binti Zahrah the Windseeker

Zahrah the Windseeker Akata Witch: A Novel

Akata Witch: A Novel Ikenga

Ikenga Who Fears Death

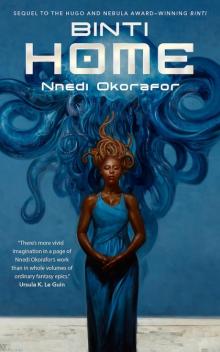

Who Fears Death Binti--Home

Binti--Home Lagoon

Lagoon Akata Witch

Akata Witch The Book of Phoenix

The Book of Phoenix Akata Warrior

Akata Warrior Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi

Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi