- Home

- Nnedi Okorafor

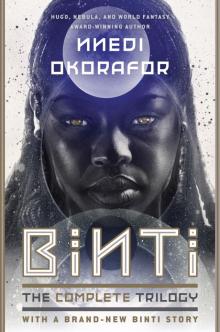

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Page 13

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Read online

Page 13

I didn’t analyze this too closely. If I went down that desert hare’s burrow, I’d find myself in a dark dark place where I asked questions like, “Who did Okwu kill during the moojh-ha ki-bira?” I understood that when Okwu had participated in the killing, it had been bound by the strong Meduse thread of duty, culture, and tradition . . . until my otjize showed it something outside of itself.

During those first months at Oomza Uni, Okwu had answered my calls and walked for miles and miles with me through Math City during the deepest part of night when I suffered from homesickness so powerful that all I could do was walk and let my body think I was walking home. It had talked me into contacting all my siblings, even when I was too angry and neglected to initiate contact. Okwu had even allowed my parents to curse and shout at it through my astrolabe until they’d let go of all their anger and fear and calmed down enough to finally ask it, “How is our daughter?” Okwu had been my enemy and now was my friend, part of my family. Still, I requested that my meals be delivered to my room.

By the second day, the flashbacks retreated and I was able to spend time with Okwu talking in the space between our dining halls.

“It’s good to be off planet again,” Okwu said.

I gazed out the large window into the blackness. “This is only my second time,” I said.

“I know,” Okwu said. “That’s why being on Oomza Uni was so natural for you. I enjoy the university with its professors and students, but for me, it’s left me feeling . . . heavy.”

I turned to it, smiling. “But you’re so . . . light already. You barely weigh . . .”

“It’s not about mass and gravity,” it said, twitching its okuoko in amusement. “It’s the way you feel about needing to be near the desert. You don’t live in it, but it’s where you run to when things get unbearable. It is always there. It is the same with me and space.”

I nodded, thinking of the desert on Oomza Uni and the one near my home. “I understand. Is that why you wanted to come with me so badly?”

It puffed out a plume of gas. “I can travel home at any time,” it said. “But the timing seemed right. The chief likes the idea of irritating the Khoush with my visit.” It shook its tentacles and vibrated its domes, laughter.

“You’re coming to make trouble?” I asked, frowning.

“Meduse like war, especially when one isn’t allowed to make war.” A ripple of glee ran up the front of its dome.

I grunted turning away from it and said in Otjihimba, “There isn’t going to be any war.”

Three Earth days. When it came time to eat, though I tried, things didn’t get any better. I took one step into the dining hall where the Meduse had performed moojh-ha ki-bira, looked around, turned and went right back to my room, and again requested my meals to be sent there.

I spent much of my time meditating in the ship’s largest breathing chamber. Most were not allowed to enter these spaces for more than a highly monitored few minutes, but my unique hero status got me whatever I wanted, including unlimited breathing room time. Okwu didn’t join me here because its gas wasn’t good for the plants, plus it didn’t like the smell of the air. For me, the fragrant aroma of the many species of oxygen-producing plants and the moist air required to keep them alive was perfect for my peace of mind. And the otjize on my skin remained at its most velvety smooth here.

The three days passed, as time always does when you are alive, whether happy or tortured. And soon, I was strapping myself in my black landing chair and watching the earth get closer and closer.

When we entered the atmosphere, the sunlight touched my skin and the sweet familiar sensation brought tears to my eyes. Then my okuoko relaxed on my shoulders as I felt the Earth’s sun shine on them for the first time. Even being what they were, my okuoko knew the feeling of home. After we landed and the ship settled at its gate, I sat back and looked out the window at the blue sky.

I laughed.

At Home

A week ago, Oomza University Relations instructed Okwu and me to wait two hours for everyone to exit the ship before we did when we arrived on Earth.

“But why?” I’d asked.

“So there is no trouble,” both of the reps we’d been meeting with had said simultaneously.

It had been over a hundred years since a Meduse had come to Khoush lands, and never had one arrived in peace. The reps told us the launch port would be cleared for exactly one hour, except for my family, representatives, officials, and media from the local Khoush city of Kokure and my hometown of Osemba. A special shuttle would drive Okwu, me, and my family to my village.

The two hours we waited allowed me to shake off my landing weakness. I wore my finest red long stiff wrapper and silky orange top, my edan and astrolabe nestled deep in the front pocket of my top. I’d also put all my metal anklets back on. I did a bit of my favorite traditional dance before my room’s mirror to make sure I’d put them on well. The fresh otjize I’d rubbed on every part of my body felt like assuring hands. I’d even rolled three of Okwu’s okuoko with otjize; this would please my family, even if it annoyed the Khoush people. To Meduse, touching those hanging long tentacles was like touching a human’s long hair, it wasn’t all that intimate, but Okwu wouldn’t let just anyone touch them. But it let me. Covering them with so much otjize, Okwu told me, made it feel a little intoxicated.

“Everything is . . . happy,” it had said, sounding perplexed about this state.

“Good,” I said, grinning. “That way, you won’t be so grumpy when you meet everyone. Khoush like politeness and the Himba expect a sunny disposition.”

“I will wash this off soon,” it said. “It’s not good to feel this pleased with life.”

We walked down the hallway and when we rounded a curve, it opened into the ship’s exit. For a moment, I could see everyone out there before they saw me. Three news drones hovered feet away from the entrance. The carpeting before the exit was a sharp red. I blinked and touched my forehead, pushing, shoving the dark thoughts away.

I spotted my family, standing there in a group, then another group of Khoush and Himba welcoming officials. I hadn’t told my family about my hair not being hair anymore, that it was now a series of alien tentacles resulting from the Meduse genetics being introduced to mine; that they had sensation and did other things I was still coming to understand. I could hide my okuoko with otjize, especially when I spoke with my family through my astrolabe where they couldn’t see how my okuoko sometimes moved on their own. Won’t be able to hide them for long now, I thought.

Any moment, I would exit and they would all see me. I slowed down and took a deep breath, let it out and took in another. I held a hand out behind me for Okwu to wait. Then I knelt down, swiped some otjize from my cheek, and touched it to the ship’s floor. My prayer to the Seven was brief and wordless but within it, I asked them to bless the Third Fish, too. “This interstellar traveling beast holds a part of my soul,” I whispered. “Please give her a safe delivery and may her child be heavy, strong, as adventurous as her mother and as lovely.” I wished the Third Fish could understand me and thus understand my thanks and I felt one of my okuoko twitch. As if in response, the entire ship rumbled. I gasped, grinning, delighted. I pressed my palm more firmly to the floor. Then I stood and walked to the exit.

I stepped out of the ship before Okwu, so the sound of my mother’s scream reached my ears immediately. “Binti!” Then there was a mad rush and I was suddenly in a crush of bodies, half of them covered in otjize (only the women and girls of the Himba use the otjize). Mother. Father. Brothers. Sisters. Aunts. Uncles. Cousins.

“My daughter is well!”

“Binti!”

“We’ve missed you!”

“Look at you!”

“The Seven is here!”

When everyone let go, I started sobbing as I clung to my mother, holding my father’s hand as he followed close behind. I ca

ught my brother Bena’s eye as he flicked one of my otjize-heavy locks with his hand. Thankfully, this didn’t hurt much. “Your hair has grown a lot,” he said. I grinned at him, but said nothing. My sisters started swinging their long thick otjize–palm rolled locks side to side and singing a welcome song, my brothers clapping a beat.

And then it all stopped. I stopped in mid-sob. My parents stopped joyously laughing. Bena was looking behind me with wide eyes, his mouth agape as he pointed. I slowly turned around. For a moment, I was two people—a Himba girl who knew her history very very well and a Himba girl who’d left Earth and become part-Meduse in space. The dissonance left me breathless.

Okwu filled the exit with its girth. Its three otjize-covered okuoko were waving about, as if in zero gravity, one of them whipping before its dome violently, as if signing some sort of insult. Its light blue semitransparent thin-fleshed dome was protected by the clear metal armor it’d created on Oomza Uni. From the bottom front of its dome protruded its large white toothlike stinger.

Behind me, I heard clattering and the sound of booted footsteps rushing into the room. When I turned, one of the Khoush soldiers had already brought forth his gun and fired it. Bam! Screams, running, someone or maybe some two were grabbing and pulling at me. I dug in my heels, yanked at my arms. A small burst of fire bloomed in the carpet at Okwu’s tentacles. Inches from Okwu, feet from the Third Fish.

“What are you doing?” I shouted. Oh no, I thought, a moan in my gut. I felt Okwu’s rage flare, a burning in my scalp, a fire igniting in me, as well. The anger. Not in front of my family! Unclean, unclean, I thought. I am unclean. Okwu made no sound or move, but I knew in moments, every soldier, maybe every one in this room would be dead . . . except possibly me. The Meduse do not kill family, but did that include “family through battle?”

I pulled from my mother’s grasp, hearing the sleeve of my top rip. I pushed my father aside, grabbed my wrapper, and lifted it above my knees. Then I ran. Past my family, dodging news drones, who turned to watch me. I flung myself in the space between Okwu and the line of soldiers that had flooded in from a doorway on the left. I let go of my wrapper and thrust my hands out, one palm facing the soldiers and the other facing Okwu.

“Stop!” I screamed. I shut my eyes. Okwu was going to strike; would it notice that it was I? Was I Meduse enough to avoid its stinger? Oh, my family. The Khoush soldiers were already shooting, the fire bullets would tear and burn me from inside out. Still, I stood up straight, my mind clear and crisp; I’d forgotten to drop into meditation.

Silence.

Eyes closed, I heard not even a footstep or rustle of someone’s garments or Okwu’s whipping tentacles. Then I did hear something and felt it, too. Oh, not here, I thought, my heart sinking as it drummed too fast and too hard. It had happened once before on Oomza Uni. I was in the forest digging up clay to make my otjize when a large piglike beast came running at me. It was too late to make a run for it, so I froze and looked it in the eyes. The beast stopped, sniffed me with its wet snout, rubbed its rough brown furry rump against my arm, lost interest, and walked off.

As I watched it disappear into a bush, I noticed my long okuoko were writhing on my head like snakes, very much like Okwu’s were now as he stood in the exit, stinger ready. I could hear my okuoko now, softly vibrating and warming. If I created a current while in this state, there would be sparks popping from the tips of each otjize-covered tentacle.

“Oh my Gods, is she part Meduse now?” I heard someone ask.

“Maybe she’s its wife,” I heard one of the journalists whisper back.

“The Himba are a filthy people,” the person said. “That’s why they shouldn’t be allowed to leave Earth.” Then there was snickering.

I met my father’s eyes and all I saw was intense raw terror. His eyes quickly moved to Okwu and I knew he was looking at its stinger. I saw the faces of my family and all the other Himba and Khoush here to welcome me and I saw the history lessons kick in as they lay their eyes on the first Meduse they had ever seen in real life.

“Okwu is—” I turned from the soldiers to Okwu and back, trying to speak to them all at the same time. “All of you . . . don’t move! If you move . . . Okwu . . . calm down, Okwu! You fight now, you kill everyone in here. These are my family, my people, as you are . . . We’ll remain alive and there will be a chance for all of us to grow as . . . as people.” Sweat beaded through the otjize on my face and tumbled down my cheeks. More silence. Then a soft slippery sound; Okwu sheathing its stinger. Thank the Seven.

“I have respected your wishes, Binti,” Okwu said coolly in Meduse.

I turned to the Khoush and spoke quickly. “This is Okwu, Meduse ambassador and student of Oomza Uni. The Pact. Remember the Pact. Have you forgotten? It’s law. Please. He is here in peace . . . unless treated otherwise. Please. We’re a people of honor, too.” As I stared forcefully at the Khoush soldiers, I couldn’t help but feel hyperaware of the otjize on my face and the fact that they probably all saw me as a near savage.

Still, after a moment, the soldier in front raised a hand and motioned for the others to stand down. I let out a great sigh of relief and lowered my chin to my chest. “Praise the Seven,” I whispered. My mother began to clap furiously, and soon everyone else did, too. Including some of the soldiers.

“Welcome to Earth,” a tall Khoush man in immaculate white robes said, sweeping in, grabbing my hand and pumping it. He spoke with the gusto of a politician who’s just had the wits scared from him. “I am Truck Omaze, Kokure’s new mayor. It’s a great honor to have you arriving at our launch port on your way home. You’re an inspiration to all of us here on Earth, but especially in this part of the world.”

“Thank you, Alhaji,” I said, politely, straining to control my quivering voice.

“These Meduse,” I heard my father tell my mother. “Look how the Khoush are afraid of just one. If I didn’t feel I was going to die of terror, I’d be laughing.”

“Shush!” my mother said, elbowing him.

“Come, let us smile to everyone.” His grin was false and his grasp was tight as he laughingly whirled me toward the news drones, without giving Okwu a single glance. The mayor smelled of perfumed oil and I was reluctant to get too close to him with his white robes. However, he didn’t seem to mind the otjize stains, or maybe he was so shaken that he didn’t care at the moment. He pulled me close as the drones moved in and his grin broadened. I felt him shudder as Okwu moved in behind us to get into the shots. And despite the fact that we’d all nearly been on the verge of death by fire bullet or stinger or both, I somehow grinned convincingly at the camera drones.

* * *

We had about forty-five minutes and both Himba and Khoush journalists sat us down right there in a vacated airport restaurant for interviews. From the questions, I gathered what the community most wanted to know.

“We are proud of you, will you stay?”

“You have befriended the enemy. Will you meet with our elders and share your wisdom?”

“What was your favorite food on Oomza Uni?”

“What are you studying?”

“What kind of fashion are you most interested in now?”

“Why did you come back?”

“They let you come back? Why?”

“Why did you abandon your family?”

“What are those things on your head? Are you still Himba?”

“You still bless with otjize, why?”

“Mathematics, astrolabes, and a mysterious object, you’re truly amazing. Will you be staying now that you’ve seen Oomza Uni, a place so much greater than your meager Himba home?”

“What was Oomza Uni like for a tribal girl like you?”

“What is that on your head? What has happened to you?”

“No man wants a girl who runs away, are you happy with your spinsterhood?”

I smiled and polite

ly answered all their questions. Then I moved right on to stiff awkward conversations with Khoush and Himba elected officials. Nothing was asked of Okwu and Okwu was pleased, preferring to menacingly loom in the background behind me. Okwu was happiest around human beings when it was menacingly looming.

I was exhausted. My temples were throbbing, my mind wanting a moment to focus on what had nearly happened with Okwu right outside the Third Fish and not getting a chance to do so. On top of all this, I still needed days to recover from the stress of traveling through space for the equivalent of three days and then the physical shift of being on Earth. Finally, when it was all done, we were escorted to the special shuttle arranged for Okwu and me. My family was offered a separate shuttle. I was glad for the solitude. As soon as I was inside, I slumped in my seat and tried not to look at Okwu clumsily squeezing and then bumbling into the shuttle that was clearly not made for its kind.

“Your land is dry,” Okwu said, turning to the large bulbous window at the back as we bulleted through the desert lands between Kokure and Osemba. “Its life is not water-based.”

“There used to be more water here,” I said, my eyes closed. “Then the climate changed and it went underground or dried up and the rains fell elsewhere.”

“I cannot understand why my people warred with the Khoush,” it said and we were quiet for a while. I too had often wondered why the Meduse fought with the Khoush and not some other tribe inhabiting the wetter parts of the world.

“But the Khoush have many lakes,” I said. “It’s us Himba who live closest to the deep desert, the hinterland. And even in my village, we have a lake. It’s pink in the sunlight because of all the salt in it.”

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade

Binti, The Complete Trilogy: Binti ; Home ; The Night Masquerade Remote Control

Remote Control Binti: The Night Masquerade

Binti: The Night Masquerade Binti--The Night Masquerade

Binti--The Night Masquerade Kabu Kabu

Kabu Kabu Binti

Binti Zahrah the Windseeker

Zahrah the Windseeker Akata Witch: A Novel

Akata Witch: A Novel Ikenga

Ikenga Who Fears Death

Who Fears Death Binti--Home

Binti--Home Lagoon

Lagoon Akata Witch

Akata Witch The Book of Phoenix

The Book of Phoenix Akata Warrior

Akata Warrior Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi

Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi